—The Clash

Under any economic, social, or political system, individuals, business firms, and organizations in general are subject to lapses from . . . otherwise functional behavior. No matter how well a society’s basic institutions are devised, failures of some actors to live up to the behavior which is expected of them are bound to occur, if only for all kinds of accidental reasons. Each society learns to live with a certain amount of such dysfunctional or mis-behavior; but lest the misbehavior feed on itself and lead to general decay, society must be able to marshal from within itself forces which will make as many of the faltering actors as possible revert to the behavior required for its proper functioning. [Emphasis added—m.o.]

—Albert O. Hirschman

When an organization, institution, or political party decays—due to corruption, cascading mistakes, or external shocks—participants in the organization are faced with two options: voice or exit. Members can rally others to expose the misbehavior and pressure the organization to get back on course. Or participants can exit, and leave for greener pastures. An individual’s choice depends on the person’s loyalty to the organization and the costs (and utility) of exit or voice.

Hirschman’s 1970 book, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970) accurately describes the situation we find ourselves in today, vis-à-vis social media. Substack, originally an email delivery service, has become a social media platform. Some high-profile writers are exiting Substack because of the Nazi problem. I’m choosing to use my voice.

The Controversy

Substack functions like a mega-bookstore. Substack enjoys top-tier branding, a vast online presence, and a simulated bookstore experience via its app.

Imagine a huge, virtual, Barnes & Noble that publishes, sells, and gives away all sorts of magazines, essays, and newsletters from famous and not-so-famous authors. Most customers receive their content delivered directly to their email inboxes; they experience one-on-one communication with their favorite writers. By contrast, Substack app users’ experiences are curated and filtered. App users’ exposure to content increasingly is shaped by the marketing choices of Substack executives.

The Substack app’s landing page offers three main tabs: home, inbox, and chat. “Home” is analogous to a bookstore’s featured books on the front table, “inbox” is the desk where you pick up a pre-ordered book, and “chat” is just random conversations to be had while you’re wandering through the bookstore. The problem started when (metaphorically speaking) the bookstore manager placed Mein Kampf on the front table next to The Handmaid’s Tale. This juxtaposition disturbed Substack customers and its authors. Controversy followed.

Substack’s shift from a (primarily) email newsletter delivery service to a (primarily) interactive social media platform generated the same kind of turbulence as Netflix encountered when it shifted from CD-mailed movies to streaming. Netflix’s CD stalwarts picked out what they wanted to see; streaming customers choose from selections the Netflix algorithm predicts they might like to see. The difference is Netflix is not promoting “Triumph of the Will” or “Hitler was a Great Guy” documentaries to its customers.

External Critics

Substack’s difficulties have been covered extensively by tech reporters, opinion writers, and other journalists. Here are some recently published commentaries:

Jonathan M. Katz’s Atlantic article, “Substack Has a Nazi Problem”, sparked the recent controversy.

An informal search of the Substack website and of extremist Telegram channels that circulate Substack posts turns up scores of white-supremacist, neo-Confederate, and explicitly Nazi newsletters on Substack—many of them apparently started in the past year. . . .

Some Substack newsletters by Nazis and white nationalists have thousands or tens of thousands of subscribers, making the platform a new and valuable tool for creating mailing lists for the far right. . .

Nazis and other violent white supremacists are ‘opportunists,’ Whitney Phillips, a professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication, told me. ‘Even if you’re pushing them off of one platform . . . they’re going to find a space that gives them the ability to do what it is they want to do.’ And in Substack, she said, ‘they have found a safe space.’

Will Oremus and Taylor Lorenz, tech reporters for the Washington Post, highlight the consequences of laissez faire content moderation.

In an era of social media clickbait and economic woes for mainstream outlets, Substack has emerged as a potent force in media and culture by billing itself as a place where anyone can start a publication, build a loyal following and make money doing it. . . .

But as it has blossomed into a home for a diverse array of voices from both right and left, the uproar over Nazis on the site shows cracks emerging in its “anything goes” ethos.

Guardian columnist John Naughton rejects so-called “free speech” justifications for the privately-held company’s choice to circulate Nazi material on their platform.

From the outset, the [Substack] founders were emphatic about their commitment to free speech. A decision to subscribe to a writer’s posts was a matter between the subscriber and the writer. The platform’s owners would apply a “high, high bar” before intervening in content. It was important that users of the platform be able to debate opposing views, etc, etc. The usual “marketplace of ideas” guff, in other words.

As one veteran journalist has noted, the correct number of Nazis on Substack is zero.

You can guess where this is heading. The platform that aspired to be “the last, best hope for civility on the internet” turns out to have a “Nazi problem”.

Katz’s Atlantic piece spotlighted a problem that had been loitering in the shadows. And a lot of Substack writers read The Atlantic, so what happened next was no surprise.

Internal critics — The writers mobilize

On December 14, two hundred fifty Substack writers issued an Open Letter to Chris Best, Jairaj Sethi, and Hamish McKenzie, the Substack founders/owners. They were asked to clarify Substack’s content moderation policy and to prevent Nazis from using the platform as a safe space for extremism and a funding opportunity for American fascism.

Substackers Against Nazis Open Letter

In the past you have defended your decision to platform bigotry by saying you, ‘make decisions based on principles not PR’ and ‘will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation.’ But there’s a difference between a hands-off approach and putting your thumb on the scale. We know you moderate some content, including spam sites and newsletters written by sex workers. Why do you choose to promote and allow the monetization of sites that traffic in white nationalism?

Your unwillingness to play by your own rules on this issue has already led to the announced departures of several prominent Substackers . . . .

As journalist Casey Newton told his more than 166,000 Substack subscribers . . . : ‘The correct number of newsletters using Nazi symbols that you host and profit from on your platform is zero.’

Ken White, a prominent First Amendment lawyer and former AUSA, was one of the main posters at the law-oriented satirical blog, Popehat. When the blog was discontinued, White amassed tens of thousands of Twitter followers under the Popehat handle. He left Twitter in December 2022, after the Musk acquisition and moved to Substack. “Popehat” has been on the internet for a long time and has a lot of fans. White:

Substack has Nazis, because of course it does. Substack is on the internet, Nazis are on the internet, and if Substack doesn’t want Nazis it has to take affirmative steps to get rid of them. Flies don’t stop coming into the house because you want them to; they stop because you get off the couch and close the screen door. Any social media or blogging platform faces this.

Novelist Margaret Atwood pointed out that Substack’s management wants to have its cake (“principles”) and eat it, too (profit off Nazis).

The question, simply put: Is Substack violating its own terms of service (see 1. above) by permitting Nazis to publish on it (see 2. above)? I’d say yes. . . .

No, Substack: You can’t have both the dystopian nightmare and “Flopsy Bunny’s Very Busy Day.” You can’t have both the terms of service you have spelled out and a bunch of individial publishers who violate those terms of service. One or the other has got to go, and hiding under the sofa and pretending it isn’t happening will not make your dilemma go away.

Between the bad press and pressure from high-profile Substackers, Management finally addressed the issue.

Minimal, face-saving action by owners

Initially, Hamish wrote a Note that further incensed Substack writers. I paraphrase: “We hear you, man. Censorship bad, Nazis bad, we good. It is what it is.” The censorship argument is the techbro/bad faith/fall-back position. It is completely wrong. Under the First Amendment, government censorship of written or spoken speech is forbidden—with some exceptions. Selectivity regarding which products to offer the public is not censorship. A private company has discretion over what to promote; owners expresses their values by directing a company’s marketing and sales. Or they reveal their moral vacuity.

Substack’s co-founders finally issued a mealy-mouthed statement and removed a handful of Nazi-oriented publications from the platform: Casey Newton, on Platformer:

Like other libertarian/capitalists/techbros, Best, Sethi, and Mckenzie want to keep their cake and eat it. Their strategy is transparent: pretend to uphold “principle” by making a small change for PR purposes. It’s just easier to let the Nazis do what they want. The owners make money because extremism has become popular; on the other hand, they lose money (in the short term) by investing in content moderation. Not to mention—blowback from the Nazis (i.e., intimidation or physical violence) will be worse than receiving harshly-worded letters from the intellectuals and academics.

Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

Revered economist Albert O. Hirschman knew a thing or two about Nazis.1 And about organizations. Hirschman wrote that organizational dysfunction and decay are common across domains and that

organizations in general are subject to lapses from . . . otherwise functional behavior.

Remaining passive when extremists violate your company’s terms of service is a lapse. The question is, what to do about it?

[L]est the misbehavior feed on itself and lead to general decay, society must be able to marshal from within itself forces which will make as many of the faltering actors as possible revert to the behavior required for its proper functioning.

Exit or voice? Stay or go? Some high-profile Substack writers are making for the exits. But where shall they go? Platform hopping may offer respite in the short run, but bad actors are opportunists. Liberal enclaves provide myriad harassment opportunities for extremists. And Nazis abhor a vacuum.

If clear-eyed intellectuals and lefties leave Substack, there will be no critical mass of opposition to extremism on the platform. Once an organizational participant has exited, the opportunity for voice is lost.

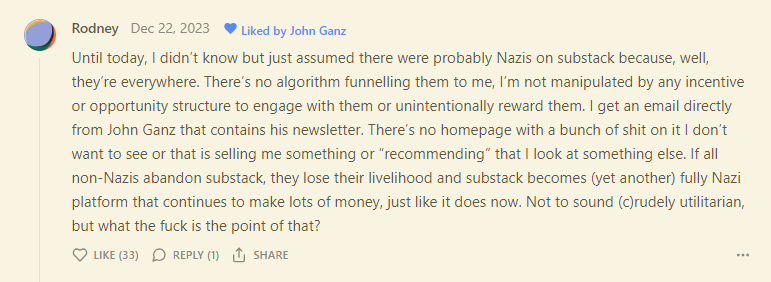

My thinking and reasons for staying are reflected in these two comments. Here’s Rodney, a subscriber to John Ganz’s Unpopular Front Newsletter:

Thomas Zimmer, the historian who writes Democracy Americana, also articulates a position that I share:

Let me start here: I understand wanting to punish Substack and not wanting to have anything to do with people who are ok with monetizing Nazis. I very much share that general sentiment. But I disagree that abandoning Substack, and doing so immediately, is the only acceptable choice . . . .

First of all, the situation on Substack is not as bad as . . . Twitter since Musk took over. On Ex-twitter, far-right trolls and aggressive extremists are omnipresent, they are going after people in swarms. . . . Over here, I generally don’t encounter any extremists. Very rarely has some rightwing asshole showed up in my comments – I’ve so far had to block fewer than ten people . . . .

I’m assuming most of my readers . . . don’t interact with Substack as a platform at all, aside from . . . their email. On Ex-Twitter, the guy in charge is himself a rightwing extremist: Musk sees himself as a brave crusader against the dangers of “wokeism” and is working tirelessly to make Twitter a more hostile environment for those he perceives to be on the “Left.” . . . But Substack is not Twitter.

[T]he experience of the past year . . . has convinced a lot of people to completely give up on all of social media. . . But that step comes at considerable cost. Here on Substack, I have found some of the smartest, most incisive, most thoughtful political and cultural analysis and commentary that exists. And much of it is coming from writers, academics, and activists who have no or little traditional backing through a big institution . . . . If they all abandoned social media entirely, the balance of power would shift dramatically away from smart, critical, leftwing and progressive perspectives. The result would be a political discourse entirely shaped by the people at big mainstream media outlets on the one hand and by reactionary centrists like Nate Silver and Matthew Yglesias . . . on the other.

Exit makes sense if there is a better organization to move to and you have exhausted all means to influence the organization from within. Voice is my choice.

And now . . . your moment of solidarity and music.

Writing—and reading—about serious subjects can be fairly depressing. Grounded will conclude each week with an upbeat piece so that you may leave with a bit of joy in your heart.

Related Grounded articles:

To The Management (December 14, 2023)

Everything Old is New Again (June 20, 2023)

Keep scrolling down (below Notes) to reach the comments, share, and like buttons.

Dear Readers, could you please hit the “like” button? It helps improve the visibility of Grounded in search results. Thanks.

Follow me on social media:

Post.News Bluesky CounterSocial Facebook

Notes:

Daniel Boffey, The punch that ‘burst the bubble’: residents of Hitler’s alpine home rise up against neo-Nazi visitors.

Chase DiBenedetto, The ongoing content moderation issues behind Substack's meltdown.

Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.

Jonathan M. Katz, Substack has a Nazi Problem.

John Naughton, Publish Nazi newsletters on your platform, Substack, and you will rightly be damned.

Will Oremus and Taylor Lorenz, Substack wanted to be neutral. Its tolerance of Nazis proved divisive.

Jacob Stern, Substack was a Ticking Timebomb

Netflix’s limited series, “Transatlantic,” is based on the true story of the Emergency Rescue Committee that worked with the French Resistance to help Jewish artists and intellectuals escape the Nazis. Albert O. Hirschman was a key member of this group and is portrayed in the fictionalized series by actor Lucas Englander. Highly recommended.

Great article! It takes courage to stand up to bullies. Running away is not the answer. I stand with you! Keep it up! I absolutely love the video!

Thanks for staying to fight for what is right. The writers who leave may believe Substack needs them more than vice-versa. But as your sources note: "where does that leave the readers / subscribers?" Hold fast and keep applying the pressure.