The tail wagging the dog. The cart before the horse. Ready, fire, aim. But enough with the cliches! Although annoying, these maxims embody time-honored principles—that good outcomes require thoughtful consideration before action, and impulsiveness makes a bad situation worse.

These truths are most relevant in the areas of crime and punishment. Here’s a typical scenario: Something bad happens. The bad thing is publicized based on preliminary, incomplete information. The inaccurately described bad thing is amplified by sensational media coverage. People react to the bad thing and their fears are magnified as public outrage mounts. Law enforcement and politicians feel increasing pressure to act quickly. The authorities also may have tunnel vision or biases that lead to misjudgments and mistakes. Authoritative action does not solve the original problem (i.e., what caused the bad thing), and the enacted public policies have second- and third-order effects that create new problems. A bad situation is now worse.

Let’s explore this scenario with a famous real-life example: the Central Park Jogger case.

Yusef Salaam was 15 years old when Donald Trump demanded his execution for a crime he did not commit. . . .

It was 1989. The crack epidemic had torn through New York as poverty soared to 25% and the city’s elites reaped the rewards of a booming Wall Street. The murder rate had risen to 1,896 killings a year; 3,254 rapes would be reported in the five boroughs, but only one captured the city’s extended attention and later exposed bias in its criminal justice system and media establishment.

In the early hours of April 20, 1989, the naked body of the “Central Park Jogger,” a brutalized rape victim was discovered in a ditch. Several hours earlier, a couple of dozen teenagers from East Harlem were running amok through Central Park; some assaulted and robbed other park-goers. Those facts are undisputed. What created the firestorm was the assumption—by law enforcement, the New York media, politicians, and the public—that the aggravated sexual assault on a female jogger and the youth mayhem earlier in the evening were connected.

What happened then?

The victim was white. The accused were black and brown. If “the eldest of that wolf pack were tried, convicted and hanged in Central Park, by June 1, and the 13- and 14-year-olds were stripped, horsewhipped, and sent to prison,” the columnist Patrick Buchanan wrote, “the park might soon be safe again for women.” Note for note, without mention of race, Mr. Buchanan and others echoed the historic calls for the public punishment of dark-skinned men thought to have defiled white women.

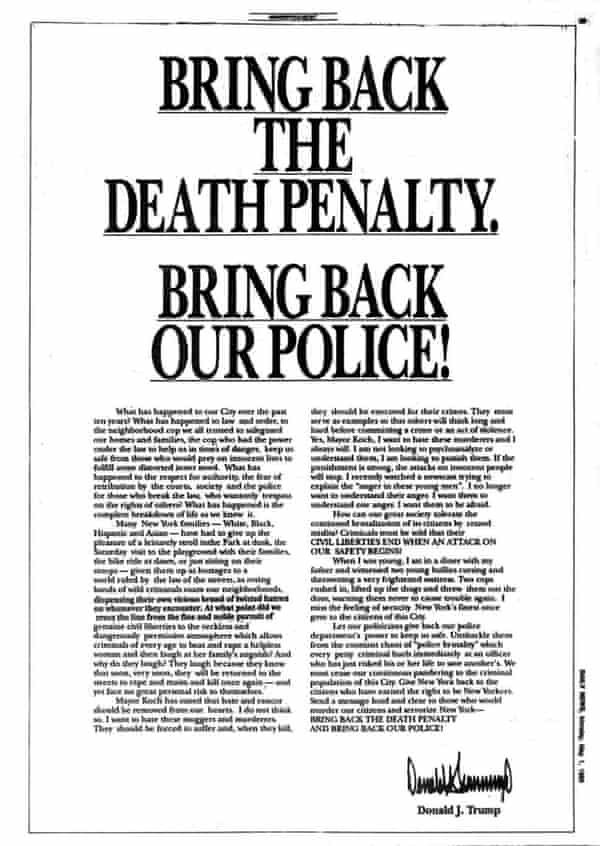

Just two weeks after the attack, Mr. Trump published his ads, headlined, “Bring Back the Death Penalty.”

Although the Black teenagers causing trouble in Central Park that night were not part of a single group or gang, and only some of the teens committed crimes, this bunch of kids was portrayed as a single, dangerous “pack.”

Newspapers, politicians, and police used language that dehumanized the Harlem youth. Commentators warned that this “wolf pack” went “wilding,” preying on law-abiding citizens.

Two days after the remaining three suspects had been arrested, the New York Post portrayed “wilding” as “packs of bloodthirsty teens from the tenements, bursting with boredom and rage, roam[ing] the streets getting kicks from an evening of ultra-violence.” Soon the term became part of the national discourse, with the newscaster Tom Brokaw describing “wilding” as “rampaging in wolf packs and attacking people just for the fun of it” on NBC Nightly News. Peter Jennings of ABC named it “terror,” plain and simple.

The concept of “wilding” and the racist assumptions behind it made it seem plausible to law-enforcement authorities and the public that black and brown boys’ mischief could easily turn into violent rape.

Prosecutions based on “racist assumptions . . . [that] seem plausible to law-enforcement authorities and the public” are inferior to prosecutions based on evidence. Despite lacking evidence against the Central Park Five, prosecutors sought—and obtained—guilty verdicts at trial.

The manifold consequences of the Central Park Jogger case unspooled for decades. These were some of the consequences:

For the individual teens who were wrongfully convicted in 1989: their lives were profoundly affected by years of incarceration. In 2002, the Five’s guilty verdicts were vacated when evidence was reexamined and a serial offender confessed to the rape of the Central Park jogger. The five exonerated men filed lawsuits against the city of New York in federal court for civil rights violations. Another civil lawsuit was brought against the State of New York for economic and emotional harm caused by the wrongful convictions. The City and the State ultimately settled the cases, paying out millions of dollars to the Central Park Five.

For the Central Park jogger who nearly died from injuries and had no memory of the attack. She never definitively found out what really had happened to her.

For New Yorkers: neither Central Park nor New York City streets were safer because the five Harlem youths were arrested. While the NYPD focused its investigation on them, the actual rapist, Matias Reyes, remained at large. He raped four more women, killed one, and was caught robbing a fifth. Reyes was sentenced to 33 years-to-life for these crimes. In 2002, confronted with new DNA evidence, Reyes confessed to the aggravated rape of the Central Park jogger for which the five teenagers had gone to prison.

A series of DNA tests proved that the man, Matias Reyes, not only had sexually assaulted the victim, but had been the only person to leave any biological evidence. He later told a defense investigator that he was remorseful after meeting Mr. [Korey] Wise in prison and seeing him suffer.

In addition, New York taxpayers footed the bill for multiple investigations, court proceedings, and the money damages paid to the unjustly convicted Central Park Five.

For the country: The language of “wilding” and fear of urban “wolf packs” generated political hysteria and knee-jerk policy changes that made the criminal justice system less fair. The political rhetoric and outrage ushered in a period of high incarceration rates with many juveniles being charged as adults.

Under the camouflage of fighting crime, politicians used coded language that ginned up racial animosity to push their agendas. In the aftermath of the Central Park Jogger prosecutions, conservative voices promulgated the “superpredator thesis” warning that demographic changes would result in a surge of violent crime. This argument was embraced by Republican and Democratic politicians alike; they passed “Three Strikes” laws that further expanded prison populations.

Politicians embraced tough-on-crime platforms and enacted harshly punitive policies. Experts warned the worst could be yet to come. Then crime rates went down. And then they kept going down.

By the decade’s end, the homicide rate plunged 42 percent nationwide. Violent crime decreased by one-third.

Crime went down and it was not because tough-on-crime policies worked. The explanation that received the most support from experts was that of behavioral economists John Donohue and Steve Levitt. They argued that the availability of legal abortion, starting in 1973 with Roe v Wade, resulted in fewer unwanted and under-resourced children maturing into their crime-prone years in the early 1990s. So the decade began with overblown public fears about superpredators and wolf packs; it ended with the Great Crime Decline.

The Central Park Five saga should be a lesson for us. It shows how sketchy initial facts can be prematurely woven into a cohesive narrative to satisfy political interests — the interests of the public to have their prejudices confirmed, the interests of the police for a speedy resolution of the mystery in a way that makes them look good, the interests of politicians who want to be seen doing something about crime in the city. None of this serves social justice or peace.

The truth came out. Reforms followed—eventually. But innocent people suffered needlessly in the process.

Maybe we should take our cliches more seriously? How about . . .

Look before you leap.

Find me on social media:

Keep scrolling down (below Notes) to reach the comments, share, and like buttons

Notes:

Ken Burns, The Central Park Five. PBS documentary.

Ava DuVernay, When They See Us. Netflix miniseries.

Jim Dwyer, The True Story of How a City in Fear Brutalized the Central Park Five (NYT unlocked/gift article).

Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn, Prosecutor is said to back dismissals in ‘89 jogger rape (NYT unlocked/gift article).

Matt Ford, What Caused the Great Crime Decline in the U.S.?

Elizabeth Hinton, How the ‘Central Park Five’ changed the history of American law.

Oliver Laughland, Donald Trump and the Central Park Five: the racially charged rise of a demagogue.

People v. Wise, 194 Misc. 2d 481, 752 N.Y.S.2d 837 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2002)

Sydney H. Schanberg, A Journey Through the Tangled Case of the Central Park Jogger.

Alex S. Vitale, The new ‘superpredator’ myth (NYT unlocked/gift article).

Wikipedia, Central Park jogger case.