Sooner or later, people get tired of lies. Some falsehoods may entertain or stimulate listeners—but the repetition is exhausting. Deceptions, untruths, deceits, and fabrications may offer temporary benefits—an adrenaline rush of outrage, a feeling of being-in-the-know, a cultish belonging. But these fleeting sensations have no utility and offer no guidance in the quotidian world. While fantasies can soothe the psyche—by affirming personal prejudice and identifying with a collective delusion—they enfold the gullible in fraud.

The conspiratorial world conjured by propagandists only has utility for them—Nazis loot, Steve Bannon grifts, and Donald Trump skates. The propaganda artist is Player One: designing the game, controlling the characters, reaping the profits. And the game works best—continually engaging the most players and generating the most money—when it creates an alternate reality feedback loop.

Over decades, America’s anti-democratic movement has developed information systems and organizational structures that project a dystopian vision of society. The rightwing narrative mixes fact and fantasy to portray the economically growing, demographically diversifying, world power United States as a putrid, decaying hellhole. Their propaganda sells this disconsolate vision by wrapping it in the flag, inciting anger, and targeting enemies. Ingesting lies and conspiracies guarantees believers a place within this fantasy world; they take shelter there and avoid contact with “the reality-based community.”

Conservative intellectuals expressed concern over the growing insularity of rightwing circles over a decade ago. Julian Sanchez of the libertarian Cato Institute described this closed conservative belief system as follows:

One of the more striking features of the contemporary conservative movement is the extent to which it has been moving toward epistemic closure. Reality is defined by a multimedia array of interconnected and cross-promoting conservative blogs, radio programs, magazines, and of course, Fox News. Whatever conflicts with that reality can be dismissed out of hand because it comes from the liberal media, and is, therefore, ipso facto not to be trusted. (How do you know they’re liberal? Well, they disagree with the conservative media!) This epistemic closure can be a source of solidarity and energy, but it also renders the conservative media ecosystem fragile.

The rightwing ecosystem did not deal with its fragility by opening up—it shored up instead. Money, lawyers, podcasters, and influencers strengthened the disinformation network and helped it grow.

Propaganda has a long history. Humans have used misinformation and deception for political ends since the ancient Greeks. For just as long, we have fought against lies and sought the truth. The only thing that has changed is the technology.

Old School, Late-Stage Propaganda

By the time I arrived in Warsaw, Communist propaganda had lost its power. Poles were tired of the Party’s lies and false promises. No matter. The censorship regime under state socialism covered publishing, economic enterprise, and politics. There was no independent press, private enterprise, or political competition.

It had been forty years since the Polish United Workers Party (PZPR) consolidated power, with the help and guidance of its Big Brother to the east, the USSR. By 1988, Communist ideology was a dead letter and propaganda was ridiculed or ignored. The regime controlled the press so the kiosks were fully stocked with newspapers and magazines.

No one purchased Trybuna Ludu (The People’s Tribune, organ of the PZPR) or Prawo i Życie (Law and Life). The popular titles were Panorama (a women’s magazine), Dziennik Polski (Polish Daily), and my local paper, Życie Warszawy (Warsaw Life). Headlines touted exciting front-page news:

At the meeting of the governmental Prezidium: evaluation of the implementation of a development program for Kraków and the voivodship

and a perennial favorite:

NATO - A Threat to Peace.

Actual news? Varsovians tuned in to the BBC or Radio Free Europe on their short-wave radios to find out what was happening in the world. Poland’s communist government had bureaucratized censorship; government journalists didn’t even try to produce interesting propaganda. People bought the daily papers for sports scores and cinema times. The newspapers were boring and the people were cynical.

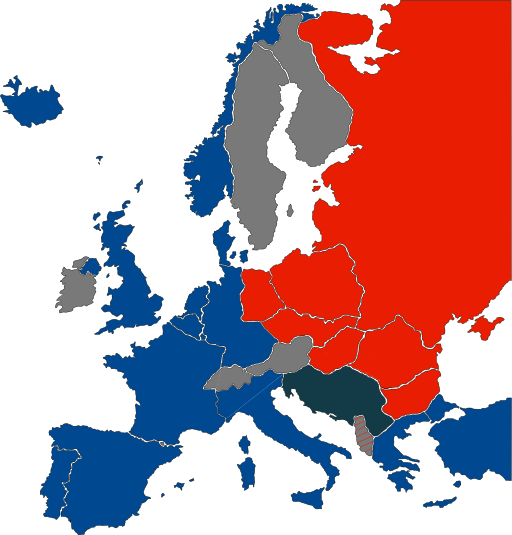

Party propaganda had been effective in the years after World War II. In 1945, Poland was in a state of exhaustion, its capital decimated by the departing Nazis. The Red Army, paused on the east bank of the Vistula River, just waited and watched as Warsaw succumbed to the flames.

After the devasting war years, a weary population wanted to believe lies about progress, about the prosperity of peasants and workers, and about the comity between Comrade Stalin and Polish Comrade Beirut. The Party was building a socialist paradise in Poland! It didn’t take long for people to distinguish between state propaganda and reality. Communist Poland wasn’t any kind of paradise—but it was still better than German or Soviet occupation.

By the late 1980s, there was no more hope for the future. The mirage of socialism had vanished. Yet a few hundred miles away, West Berlin stood as a constant, colorful, vibrant example of fun, freedom, and shopping. No matter. Communist propaganda had served its purpose—it provided a launching pad for Party leadership to consolidate power, suppress independent speech, and expand the coercive organs of the state.

It took almost half a century for that system to break down.

How Do the Pros Do It? Soviet Russian Propaganda Disinformation Operations

Who believes what and why? Here’s my handy analogy:

Russia’s official narrative acts like an information umbrella over the nation. The ribs are the various state-run media like Tass (wire service), RT (Russian Television), and Rossiyskaya Gazeta, the government’s newspaper of record.

The panels are the contents that are woven into a stretchable fabric of selected facts, half-truths, distortions, and lies.

The outer canopy acts as a barrier to information coming from the outside: from international reports, foreign news, and any source that contradicts the official narrative.

The inner canopy is the protective shield, things that people want to believe (irrespective of their truth value) because they confirm long-standing beliefs, amplify grievances, or reinforce an identity.

And the shaft is . . . self-explanatory.

Remember when Russia invaded Ukraine a couple of years ago? And Putin made a big deal about not calling it a war? The umbrella model demonstrates how the official narrative (i.e., Russian propaganda) preemptively diffused opposition to the war. Because it’s not a war! (according to Vlad).

Russia launches ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine

MOSCOW, February 24. /TASS/ On the morning of February 24, Russia officially launched a “special military operation” against Ukraine, designed, as Russian President Vladimir Putin explained, to “demilitarize” and “denazify” the neighboring state. The goal of the operation is to protect the people of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics (DPR and LPR), he said.

The anchoring idea of the official narrative, “special military operation,” spreads through the ribs of the umbrella. Other conceptual threads are woven through the umbrella’s connecting panels: for example, assertions that Russia’s goal is to de-Nazify the Ukrainian government and that Ukraine and the West are involved in an “anti-Putin” coalition. These elaborations form a cover story that becomes progressively more complicated and detached from reality.

Why not just admit Russia’s in a war? Ah, because war drags on, it expands the circle of harm. Mothers lose sons, wives lose husbands, and children lose fathers. Even more: a War in Europe—for Russians—means collective sacrifices. But a special operation suggests something professional, precise, targeted, and quick. It is a matter for the military—not for the whole society.

So the “special military operation” designation must be maintained and protected. This is the prime directive. Opposition to this narrative will be met with threats, coercion, and repression.

Cleanup in the information space began immediately.

The editor of one of the last independent newspapers, Novaya Gazeta, saw the writing on the wall.

“We continue to call war, war,” Dmitry Muratov, the editor of Novaya Gazeta, said. “We are waiting for the consequences.”

What kind of consequences are we talking about? American journalist Megan Stack, based in Moscow for a couple of years, found out. Stack’s reporting on the (alleged) murderer Andrei Lugovoi, a Russian intelligence officer who (allegedly) poisoned defector Alexander Litvinenko in London, came to the attention of Russian authorities. Stack blithely assumed that her status as a foreign journalist protected her from political retaliation. And then she received a summons.

I was questioned at a sprawling maze of a police station. The policewoman inquired about my editors and interview method. Again, she demanded my notes. Again, I refused.

I asked if we were finished.

The Man spoke up: “We haven’t started yet.”

Megan Stack was lucky. Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was not.

Do you think that Americans are immune to Russian disinformation? That Putin’s umbrella doesn’t open across oceans?

From Steven Brill and the researchers at NewsGuard:

Russia employs a multilayered strategy to introduce, amplify, and spread false and distorted narratives across the world – relying on a mix of official state media sources, anonymous websites and accounts, and other methods to distribute propaganda that advances the Kremlin’s interests and undermines its adversaries. . . . Its government-funded and operated websites use digital platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and TikTok to launch and promote false narratives.

Allow me to put forward a proposition: The purpose of Soviet Russian propaganda misinformation has not changed—but new technology has made it far more dangerous.

To be continued . . .

And now your moment of . . . real recycling.

Writing—and reading—about serious subjects can be fairly depressing. Grounded will conclude each week with a lighter story so that you may leave with a bit of joy in your heart.

Chicago has its Pothole Picasso, now meet Atlanta’s Magnet Man, Alex Benigno

Alex donates the debris his magnets pick up to Laura Lewis, a scrap metal artist.

‘When he dropped it all off, it was like he’d brought me a bunch of 100,000-piece puzzles with no pictures and no box’, she said.

‘I’m still sorting through it, and he’ll soon be bringing more,’ said Lewis, 49. ‘I’m thankful that he’s picking up scrap. It gives me hope to know someone’s out there, cleaning up after people and taking action.’

Related Grounded articles:

Lies and Lying Liars (February 18, 2022).

Why Facts Matter (March 1, 2022).

Propaganda на русском (March 4, 2022)

Keep scrolling down (below Notes) to reach the comments, share, and like buttons.

Dear Readers, could you please hit the “like” button? It helps improve the visibility of Grounded in search results. Thanks.

Follow me on social media:

Notes:

Paul Campos, Propaganda works.

Patricia Cohen, Epistemic closure? Those are fighting words.

Julian Sanchez, Frum, Cocktail Parties, and the Threat of Doubt.

Megan Stack, In Russia, I learned, threats were always real.

Ron Suskind, Faith, Certainty, and the Presidency of George W. Bush.

Wall Street Journal, Evan Gershkovich: Updates on the WSJ Reporter Detained in Russia

Wikipedia, Epistemic closure.

Further Reading:

Robyn Barrow, QShaman’s Ragnarök: An Iconography of Extremism

Umberto Eco, Ur-Fascism. Commentary and pdf here.

Decided to check out your Substack after we followed each other on Bluesky. Restacked it. Great article.

So frustrating! Thanks for the Magnet Man. gives me hope!