Sitting in the doctors’ lounge with my brother on Sunday morning is one of my earliest memories. Sunday was Mom’s day to sleep in, so Dad took us to the hospital and parked us in the lounge while he made rounds. Then he took us to Mass. (Mom was still a Protestant then, so she was off the hook for that obligation.)

I’ve been thinking about how different my Dad’s life as a doctor was in the 1960s and 1970s compared to contemporary physicians. Admittedly, my perspective isn’t in-depth or complete—especially considering the differentiation of 21st-century medical practices and specialties. I glimpse into that world. But even my partial view makes me think that today’s medical doctors are in a worse situation. Dad worked seven days a week, assisted in surgery, delivered babies, and made house calls—but he didn’t seem as stressed as my doctors are today.

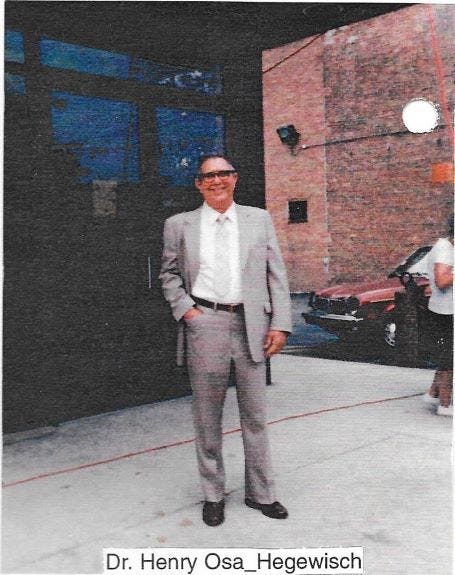

My memory may not be totally accurate, but I do remember we didn‘t see him that much and this is why: Dad usually got up at 5 am, went to the hospital to make rounds, assist Dr. Temple in surgery, and attend staff or committee meetings. Sometimes he came home for lunch or he went to the YMCA to meet his buddies for a noontime volleyball game. In the afternoons and evenings (except for Wednesdays!), Dad saw patients at his office in Hegewisch, a mostly Polish neighborhood on Chicago’s southeast side near the steel mills and the Ford plant.

On the staff of the South Chicago Community Hospital, Dad also drew patients from the South Chicago neighborhood that was predominantly Hispanic. A Cuban, he communicated easily in Spanish with the predominantly Mexican workers. Most of the patients who came to his Hegewisch office, though, were Polish.

During the 1960s, Dad didn’t see patients by appointment. His “girl” opened the waiting room at 1 pm and locked the door at 5. Whoever was in the waiting room during those hours saw the doctor. Dad took himself out to a local restaurant for dinner and then went back to the office to see patients until about 8:30. Frequently, he made house calls on the way home, to see (mostly elderly) people who were too sick to come to the office. He got home around 9:30 or 10 pm. We had already eaten dinner with Mom. Wednesday was the Universal Doctor Day Off. Dad liked to go downtown, eat a leisurely lunch at the Palmer House, stop at the cigar store on Wabash Avenue, and maybe browse through Kroch’s & Brentano’s bookstore. If school wasn’t in session, he often took one of us kids with him for company. Dad was home by late afternoon on Wednesdays so Mom often cooked Cuban food for dinner. Saturdays were a half-day of work: hospital rounds, and then 9 - 1 pm in the office. On Saturday night, my parents got a babysitter for us; they got dressed up, and they went out. Seriously. They enjoyed peak Chicago nightlife: Mister Kelley’s, the Empire Room, or the London House. They saw Frank Sinatra, Jack Benny, and Shecky Greene.

I don’t think Dad ever talked to an insurance company representative on the phone. No one questioned him about medical decisions. He was never sued. As a GP, he treated a lot of everyday illnesses and health problems: upper respiratory infections, hypertension, ingrown toenails, cuts and bruises of kids who fell off their bikes, and he did obstetrics probably until about 1966 or 1967. In thirty-one years of practicing medicine, my Dad cared for three generations in many families. People knew him. Dr. Osa didn’t always get paid but he always got respect.

A famous family story concerns a patient who was well-known for her consistent alcoholic intake. Here’s Dad recounting this tale in his “Reminiscences” (1998) that he wrote with my sister Nancy’s editorial assistance:

I will not talk about the sad cases that are the majority of a doctor’s work, but occasionally we deal with some funny ones. I had an old patient in her seventies. She and her husband used to own a tavern with living quarters on the second floor. When her husband died, she sold the tavern but still kept her residence upstairs. She had several chronic illnesses. . . she was also addicted to alcohol, which was easy to obtain from her old tavern on the first floor.

One afternoon, during my office hours when I was very busy, my secretary told me I had an emergency call from Mary. When I answered the phone, I asked what was her problem. She told me, “Dr. Osa come right away, I’m dead.” I told her “If you are already dead, you do not need me. You should call Frank Opyt [the funeral director across the street].” And she replied, “I already did, but his line was busy!”

I convinced her that she was not dead and I would see her later, which I did. Of course, she was under the influence. She recovered and was still living when I retired.

Sometimes when Rick and I went to Dad’s office, we were sent on errands to Klucker’s pharmacy—for penicillin and cigars. This local pharmacy was a Hegewisch institution and Dad did his part to sustain their business. Here’s a photo of Klucker’s in the early days before we got there:

And here’s a description of the drugstore in the 50s and 60s:

For a while, Klucker’s was as much a general store as it was a drug store. Pencils, mercurochrome, comic books, boxes of Valentine’s Day candy, and more could be found on the shelves. The white and blue mosaic tile clicked as you walked around the store. Many fondly remember the well-stocked cigar display—a favorite haunt of Doctors Osa and Zelazny.

Hegewisch was more like a close-knit village than it was a Chicago neighborhood. The populated area was surrounded by wetlands and train tracks so it was physically cut off from the rest of the city. The train crossing at 130th and Torrence was notorious; it was known for its long delays and traffic back-ups. When the steel mills and factories started closing in the 1970s, things went downhill. People lost insurance and stopped coming to the doctor for physicals and regular check-ups. The economy was changing and so was medicine.

I can’t tell how much pressure my doctors are under these days. But I do know that Tom and I “lose” primary care physicians every couple of years. Some retire, some move away or just quit. Same thing with gynecologists.

The changes in healthcare have been well documented—but this article draws not on my research but on my recollections and experiences.

I have wonderful doctors and I worry about them. They seemed stressed, always pressed for time; they know that the medication they prescribe may or may not be available to me due to cost, and they seem torn trying to get notes into the Epic software and talk to me at the same time. I feel bad if there something going on with me that’s complicated because it will take time to explain. Paradoxically, I’m very happy with my healthcare. My doctors know what they’re doing, they’re trying to get the best data they can from tests, and they consider my input and concerns as valid. This was not necessarily the case “back in the day.”

Being a doctor is a hard job . . . and it seems to have gotten harder.

No notes this week. Scroll down to reach the share, like, and comment buttons.

I enjoyed reading your reflections. My dad and yours had a lot in common both being foreign medical graduates. I miss a lot about those days when it was more about caring for our patients than having to make hospital administrators happy.

I also enjoyed reading your reflections and would love to read your dad’s, too. I have warm memories of him as my doctor when I got chicken pox. The closest thing to a Family Doctor now is La Clinica...the poor folks health providers.